Two Degree-of-freedom de Leon-Berne Model

Introduction

Development of the Problem

We will consider the two degrees-of-freedom Hamiltonian for a unimolecular conformational isomerization introduced and studied extensively by De Leon and co-authors [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. This 2 degrees-of-freedom Hamiltonian is given by H(x,y,px,py)=T(px,py)+VDB(x,y)=p2x2ms+p2y2ms+VDB(x,y)

and we will focus on varying λ and ζ.

The underlying Hamiltonian vector field is given by ˙x=∂H∂px=pxms˙y=∂H∂py=pyms˙px=−∂H∂x=2Dxλexp(−λx)(exp(−λx)−1)+V‡y4wζλy2(y2−2y2w)exp(−ζλx)˙py=−∂H∂y=−4V‡y4wy(y2−y2w)exp(−ζλx)

The total energy will be denoted by H(x,y,px,py)=E=Esaddle+ΔE where ΔE is the excess energy above the isomerization barrier energy.

The equilibrium points are located at ¯qs=(0,0,0,0) and at ¯qc=(xeq,±yw,0,0) where the x-coordinate, xeq, needs to be obtained using numerical root solver.

The total energy of the equilibrium point ¯qs is H(¯qs)=ϵs for all parameter values, and will be referred to as the critical energy. The total energy of the equilibrium point ¯qc is given by

H(¯qc)=Dx(1−exp(−λxeq))2−V‡exp(−ζλxeq)+ϵsWhen ζ=0, the equilibrium point ¯qc is at (0,±yw,0,0), and has total energy ϵs−V‡ (see Supplemental material for details).

Potential energy function

VDB(x,y)=Dx[1−exp(−λx)]2+V‡y4wy2(y2−2y2w)exp(−ζλx)+ϵsIn this study, we fix μ=8,Dx=10,yw=1/√2,V‡=1,ϵs=1, and vary the parameters ζ,λ.

The equilibrium point is at (0,0,0,0) for all parameter values and the two equilibrium points are at (xeq,±yw,0,0) which needs to be calculated using a numerical root solver and depends on Dx,yw,V‡,ζ,λ. The equilibrium point at (0,0,0,0) has energy E(0,0,0,0)=ϵs. While the equilibrium point at (xeq,±yw,0,0) has total energy

The total energy of the equilibrium points at (xeq,±yw,0,0) is H(xeq,±yw,0,0)=E(xeq,±yw,0,0)=VDB(xeq,±yw,0,0)=Dx[1−exp(−λxeq)]2−V‡exp(−ζλxeq)+ϵs

\centering \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.32\textwidth]{./figures/pe_contour_param_fig3-A1}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.31\textwidth]{./figures/pe_contour_param_fig3-A2}} \

[[fig:pecontours_fig3db1981]]{#fig:pecontours_fig3db1981 label="fig:pecontours_fig3db1981"}

REPEATED SECTION

Two DoF de Leon-Berne system

We will consider the two degrees-of-freedom Hamiltonian for a unimolecular conformational isomerization introduced and studied extensively by De Leon and co-authors [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. This 2 degrees-of-freedom Hamiltonian is given by \begin{aligned} \mathcal{H}(x,y,p_x,p_y) =& T(p_x, p_y) + V_{\rm DB}(x,y) \\ =& \frac{p_x^2}{2m_s} + \frac{p_y^2}{2m_s} + V_{\rm DB}(x,y) \end{aligned} \label{eqn:ham_db}

and we will focus on varying λ and ζ.

The underlying Hamiltonian vector field is given by \begin{aligned} \dot{x} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial p_x} &= \frac{p_x}{m_s} \\ \dot{y} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial p_y} &= \frac{p_y}{m_s} \\ \dot{p_x} = - \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial x} &= 2 D_x \lambda \exp(-\lambda x) (\exp(-\lambda x) - 1) + \\ & \qquad \dfrac{\mathcal{V}^{\ddagger}}{y_w^4}\zeta \lambda y^2(y^2 - 2y_w^2)\exp(-\zeta \lambda x)\\ \dot{p_y} = -\frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial y} &= -4 \dfrac{\mathcal{V}^{\ddagger}}{y_w^4}y(y^2 - y_w^2)\exp(- \zeta \lambda x) \end{aligned} \label{eqn:vec_field_db}

The total energy will be denoted by H(x,y,px,py)=E=Esaddle+ΔE where ΔE is the excess energy above the isomerization barrier energy.

The equilibrium points are located at ¯qs=(0,0,0,0) and at ¯qc=(xeq,±yw,0,0) where the x-coordinate, xeq, needs to be obtained using numerical root solver.

The total energy of the equilibrium point ¯qs is H(¯qs)=ϵs for all parameter values, and will be referred to as the critical energy. The total energy of the equilibrium point ¯qc is given by

H(¯qc)=Dx(1−exp(−λxeq))2−V‡exp(−ζλxeq)+ϵsWhen ζ=0, the equilibrium point ¯qc is at (0,±yw,0,0), and has total energy ϵs−V‡ (see Supplemental material for details).

{width="33.0000%"}\

{width="33.0000%"}\

{width="33.0000%"} [[fig:pecontours_db]]

Fig. 1. Potential energy function for the De Leon-Berne model of unimolecular isomerization for 3 different sets of coupling and range parameters used in~\citeauthor{de_leon_intramolecular_1981}~\cite{de_leon_intramolecular_1981}. It is to be noted that the potential energy surface is ``mostly'' flat and then becomes steep for large x<0. The coordinates of the saddle equilibrium point are also independent of the parameters and located at the origin.

REPEATED SECTION

Revealing the phase space structure

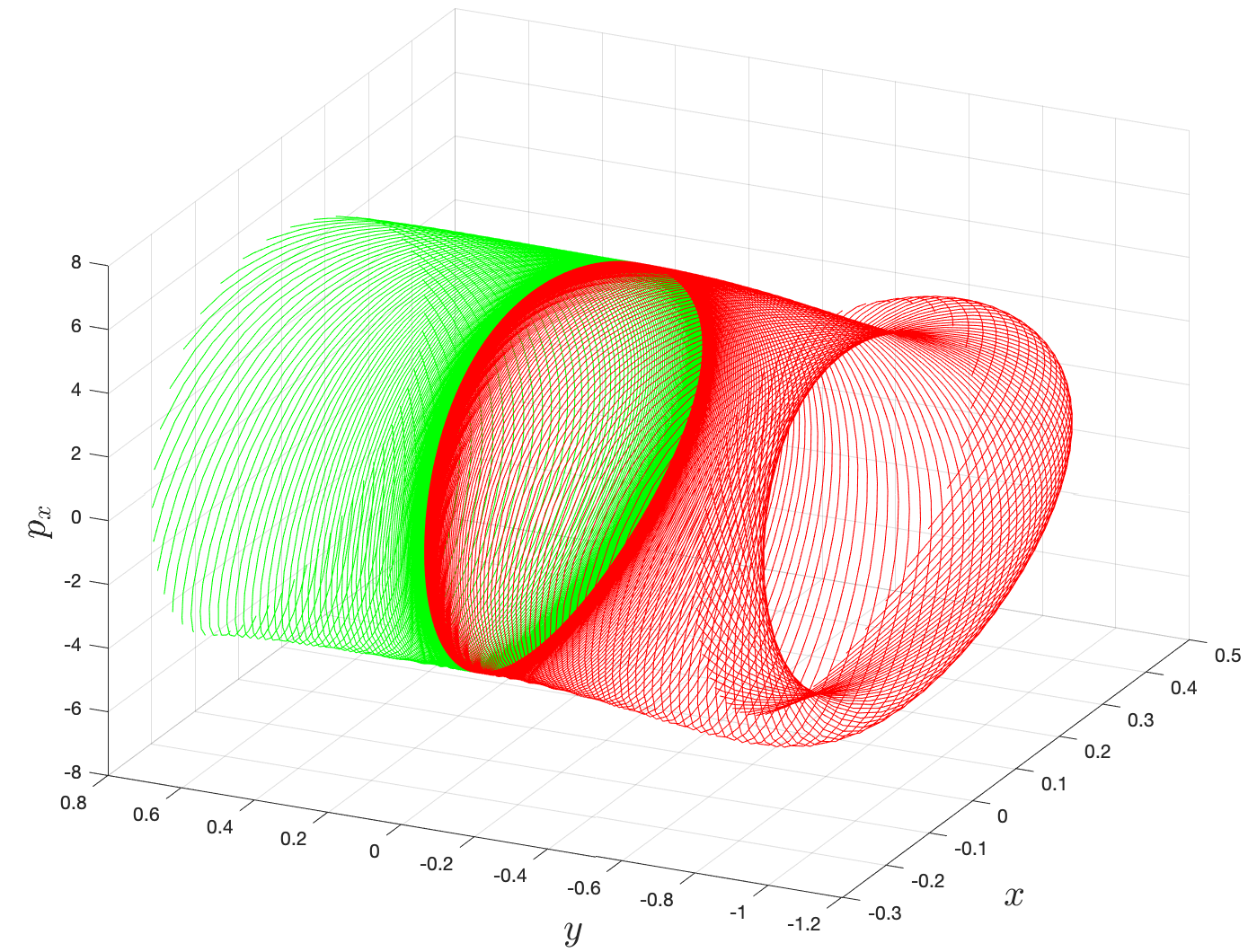

Invariant manifolds and unstable periodic orbits {#sect:tubes_transition}

We consider the dynamics of conservative system by determining the phase space "skeleton" that governs transition between potential well (or, equivalently escape from a well). In the simplest case of only two degrees of freedom, the phase space is of 4 dimensional and the boundary between potential wells is defined using unstable periodic orbit that lie in the bottleneck connecting the wells. The set of all states leading to escape from a potential well can be understood as residing within an invariant manifold of geometry R1×S1, that is a cylinder or tube. The interior of this tube defines the set of all states which will transition to the adjacent well.

Linearization near the rank-1 saddle

It is to be noted that the linearization of the behavior of trajectories near the saddle-center equilibrium points appears in the leading order expression of the transition fraction. We are interested in trajectories which have an energy just above that of the critical value. The region of possible motion for E>Ec contains a neck around each saddle equilibrium point. The geometry of trajectories close to the neck region is studied by considering the linearized equations of motion near the equilibrium point.

In this section, let xeq denote the equilibrium point connecting the top and bottom wells. Furthermore, for a fixed energy E, we consider a neighborhood of xeq on the energy surface, whose configuration space projections are the bottleneck regions. We refer to this neighborhood as the equilibrium region and denote it by R on the energy surface. We perform a coordinate transformation with xeq=(xeq,yeq,0,0) as the new origin, and keep the first order terms, we obtain ˙x=J(xeq)xwhere,x=[x,y,px,py]T

Thus, the linearized vector field at the equilibrium point becomes ˙x=J(xeq)x=Df(xeq)=(001/μ00001/μ−2Dxλ20000800)x

where f denotes the Hamiltonian vector field. which has eigenvalues of the form λ,−λ,iω,−iω given by −√2ϵμA,√2ϵμA,i√2Dxmλ,−i√2Dxmλ,

Numerical method for computing reactive islands

Step 1: Select appropriate energy above the critical value For computing the unstable periodic orbits and its invariant manifolds that are phase space conduits for transition between the two isomers, we have to specify a total energy, E, that is above the energy of the index-1 saddle (this is referred to as critical energy or reference energy or isomerization energy, Ec, in the chemical reaction dynamics literature) and so the excess energy ΔE=E−Ec>0. This excess energy can be arbitrarily large as long as the unstable periodic orbit does not bifurcate.

Step 2: Compute the unstable periodic orbit associated with the rank-1 saddle We consider a procedure which computes unstable periodic orbits associated with rank-1 saddle in a straightforward fashion. This procedure begins with small "seed" initial conditions obtained from the linearized equations of motion near xeq, and uses differential correction and numerical continuation to generate the desired periodic orbit corresponding to the chosen energy E [6]. The result is a periodic orbit of the desired energy E of some period T, which will be close to 2π/ω where ±ω is the imaginary pair of eigenvalues of the linearization around the saddle point.

Guess for initial condition of a periodic orbit The general solution of linearized equations of motion (Eqn. [eqn:linearSol]{reference-type="eqref" reference="eqn:linearSol"}) at the equilibrium point xeq can be used to initialize a guess for an iterative correction procedure called differential correction. The linearization yields an eigenvalue problem Av=γv, where A is the Jacobian matrix evaluated at the equilibrium point, γ is the eigenvalue, and v=[k1,k2,k3,k4]T is the corresponding eigenvector. We initialize the guess for the periodic orbit for a small amplitude, Ax<<1. Let β=−Ax/2 and using the eigenvector spanning the center subspace, we can guess the initial condition to be ˉx(0)=ˉx0,g=(x0,g,y0,g,px0,g,py0,g)T=(xeq,yeq,0,0)T+2Re(βuiω)=(xeq−Ax,yeq,0,0)T

Differential correction of the initial condition In this iterative correction procedure, we introduce small change in the guess for the initial condition such that coordinates at the final and initial time of the periodic orbit ‖ˉxpo(T)−ˉxpo(0)‖<ϵ

Let us denote the flow map of a differential equation ˚x=f(x) with an initial condition x(t0)=x0 by ϕ(t;x0). Thus, the displacement of the final state under a perturbation δt becomes δˉx(t+δt)=ϕ(t+δt;ˉx0+δˉx0)−ϕ(t;ˉx0)

This procedure yields an accurate initial condition for a periodic orbit of small amplitude Ax<<1, since our initial guess is based on the linear approximation near the equilibrium point. It is also to be noted that differential correction assumes the guess periodic orbit has a small error (for example in this system, of the order of 10−2) and can be corrected using first order form of the correction terms. If, however, larger steps in correction are applied this can lead to unstable convergence as the half-orbit overshoots between successive steps. Even though there are other algorithms for detecting unstable periodic orbits, differential correction is easy to implement and shows reliable convergence for generating a dense family of periodic orbits (UPOs) associated with the rank-1 saddle at arbitrary high excess energy (as long as UPOs don't bifurcate). These unstable perioidic orbit at high excess energy are required for constructing codimension−1 invariant manifolds.

Numerical continuation to periodic orbit at arbitrary energy The above procedure yields an accurate initial condition for a unstable periodic orbit from a single initial guess. If our initial guess came from the linear approximation near the equilibrium point, from Eqn. [eqn:linearSol]{reference-type="eqref" reference="eqn:linearSol"}, it has been observed in the numerics that we can only use the differential correction procedure for small amplitude (∼10−4) periodic orbit around xe. This small amplitude corresponds to small excess energy, typically ∼10−2, and to find an unstable periodic orbit of arbitrarily large amplitude, we resort to the procedure of numerical continuation to generate a family which reaches the appropriate energy E. Numerical continuation uses the two small amplitude periodic orbits obtained from the differential correction procedure and proceeds as follows.

Suppose we find two small nearby periodic orbit initial conditions, ˉx(1)0 and ˉx(2)0, correct to within the tolerance d, using the differential correction procedure described above. We can then generate a family of periodic orbits with successively increasing amplitudes associated with the rank-1 saddle ˉxe in the following way. Let Δ=ˉx(2)0−ˉx(1)0=[Δx0,Δy0,0,0]T

Step 3: Computation of invariant manifolds. First, we find the local approximation to the unstable and stable manifolds of the periodic orbit from the eigenvectors of the monodromy matrix. Next, the local linear approximation of the unstable (or stable) manifold in the form of a state vector is integrated in the nonlinear equations of motion to produce the approximation of the unstable (or stable) manifolds. This procedure is known as globalization of the manifolds and we proceed as follows

First, the state transition matrix Φ(t) along the periodic orbit with initial condition ˉx0 can be obtained numerically by integrating the variational equations along with the equations of motion from t=0 to t=T. This is known as the monodromy matrix M=Φ(T) and the eigenvalues can be computed numerically. The theory for Hamiltonian systems (see Ref. [8] for details) tells us that the four eigenvalues of M are of the form λ1>1,λ2=1λ1,λ3=λ4=1

Step 4: Reactive islands and committor probabilities In Ref. (missing reference), the authors discussed the role of reactive islands (RI) in sampling a rare trajectory and the sensitivity of the committor probability to the geometry of the RI structure.

Implications for Reaction Dynamics

Direct numerical computation of reactive islands

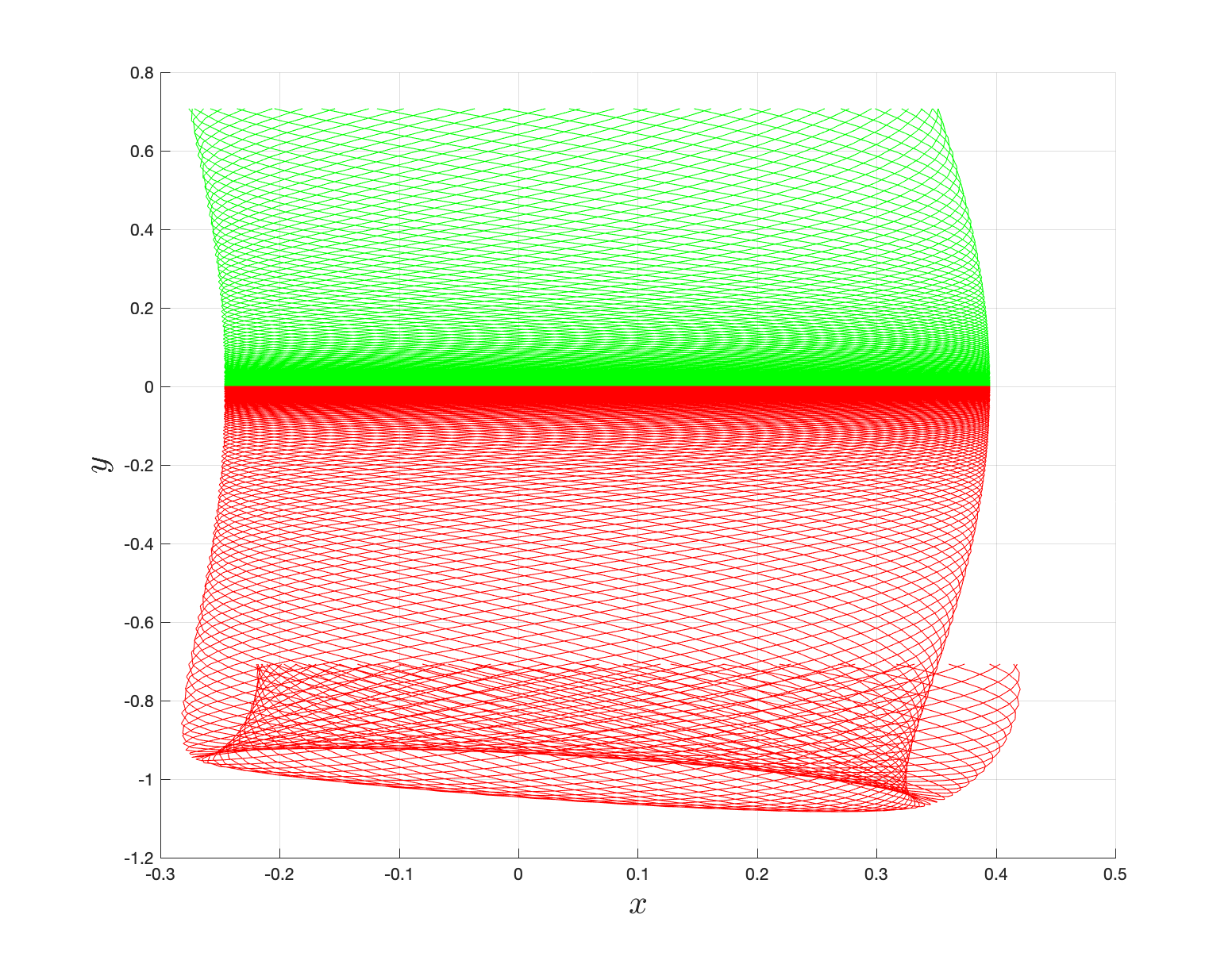

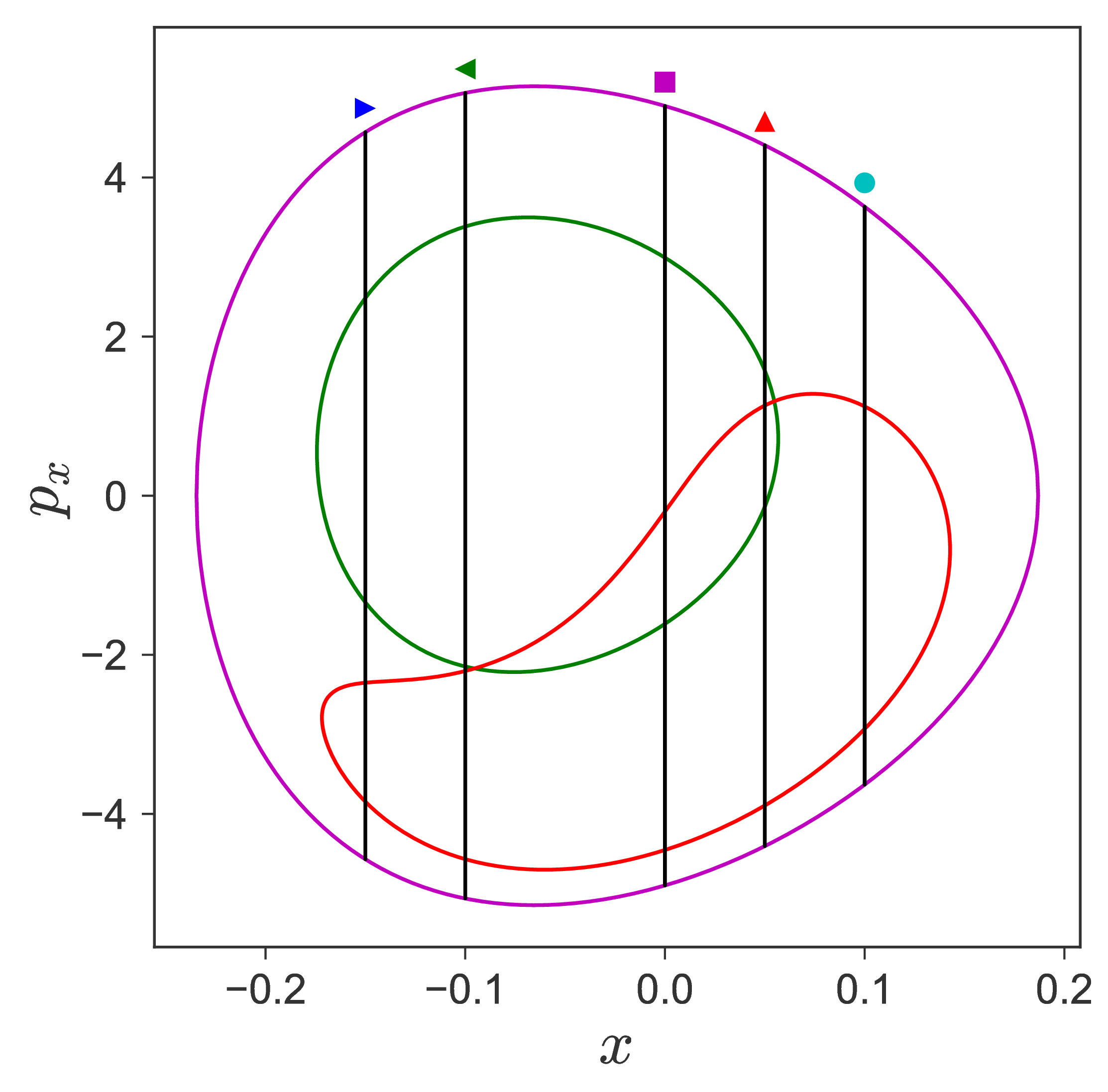

{width="45%"}\

{width="45%"}\  {width="45%"}

{width="45%"}

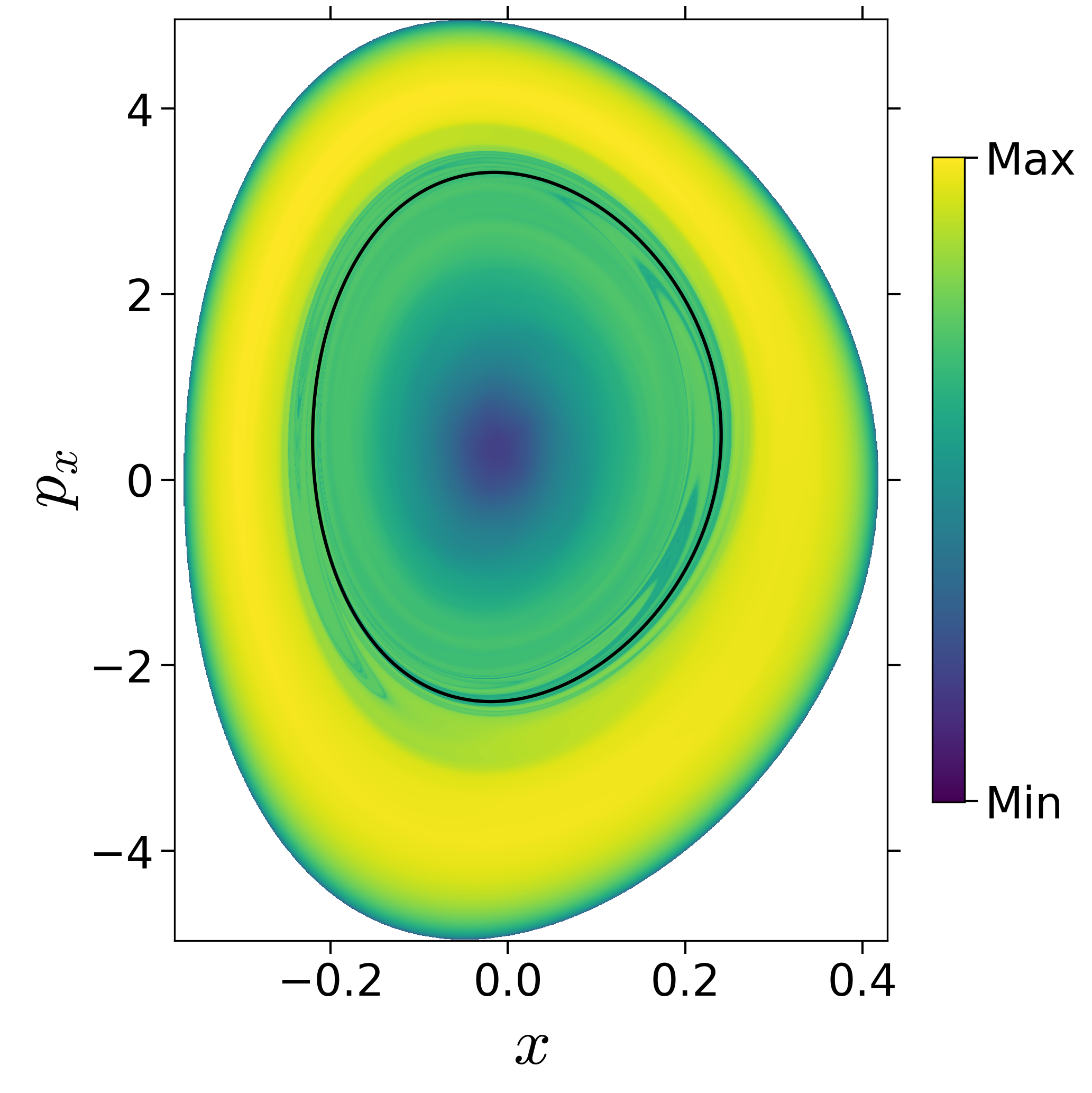

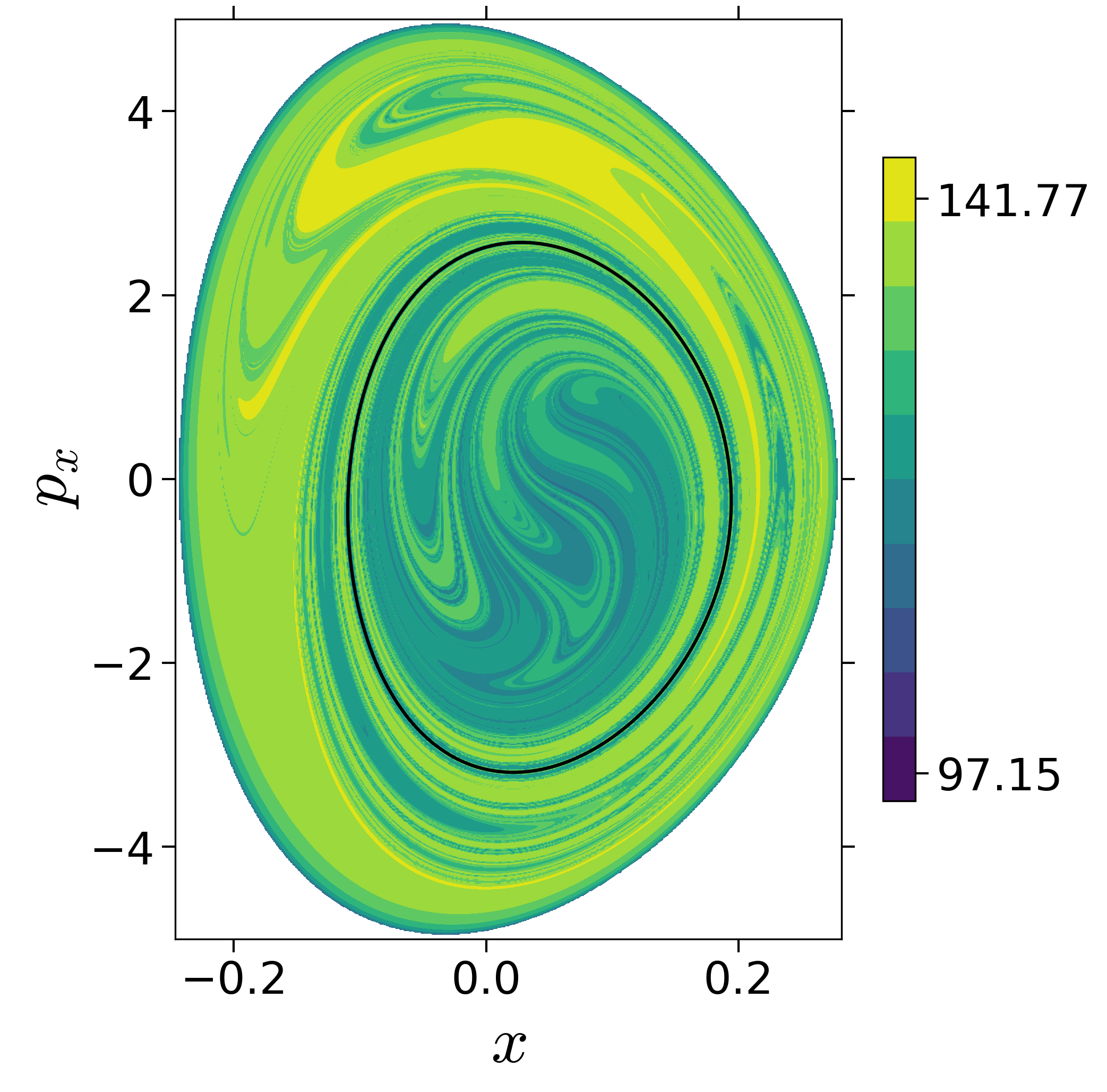

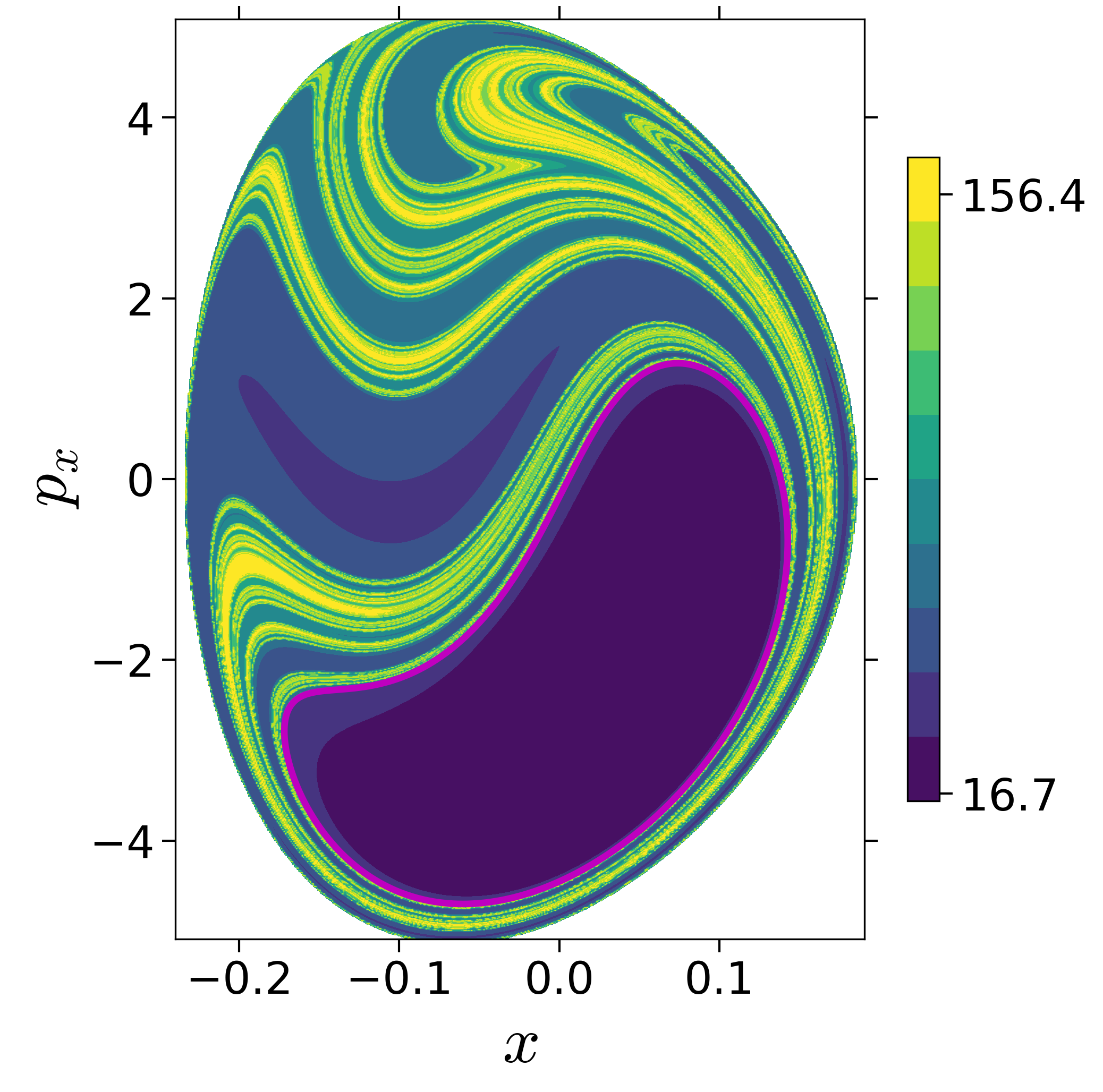

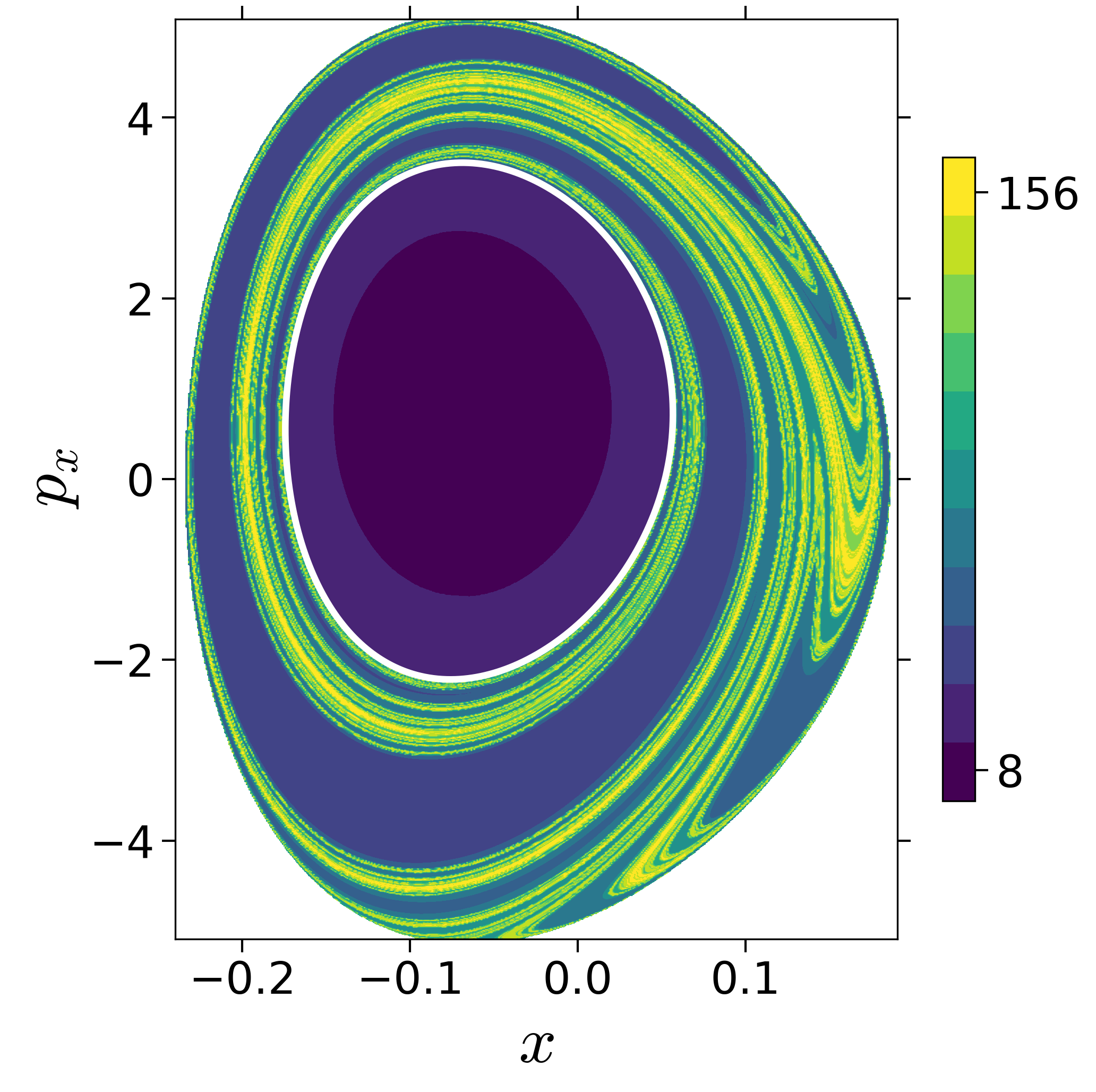

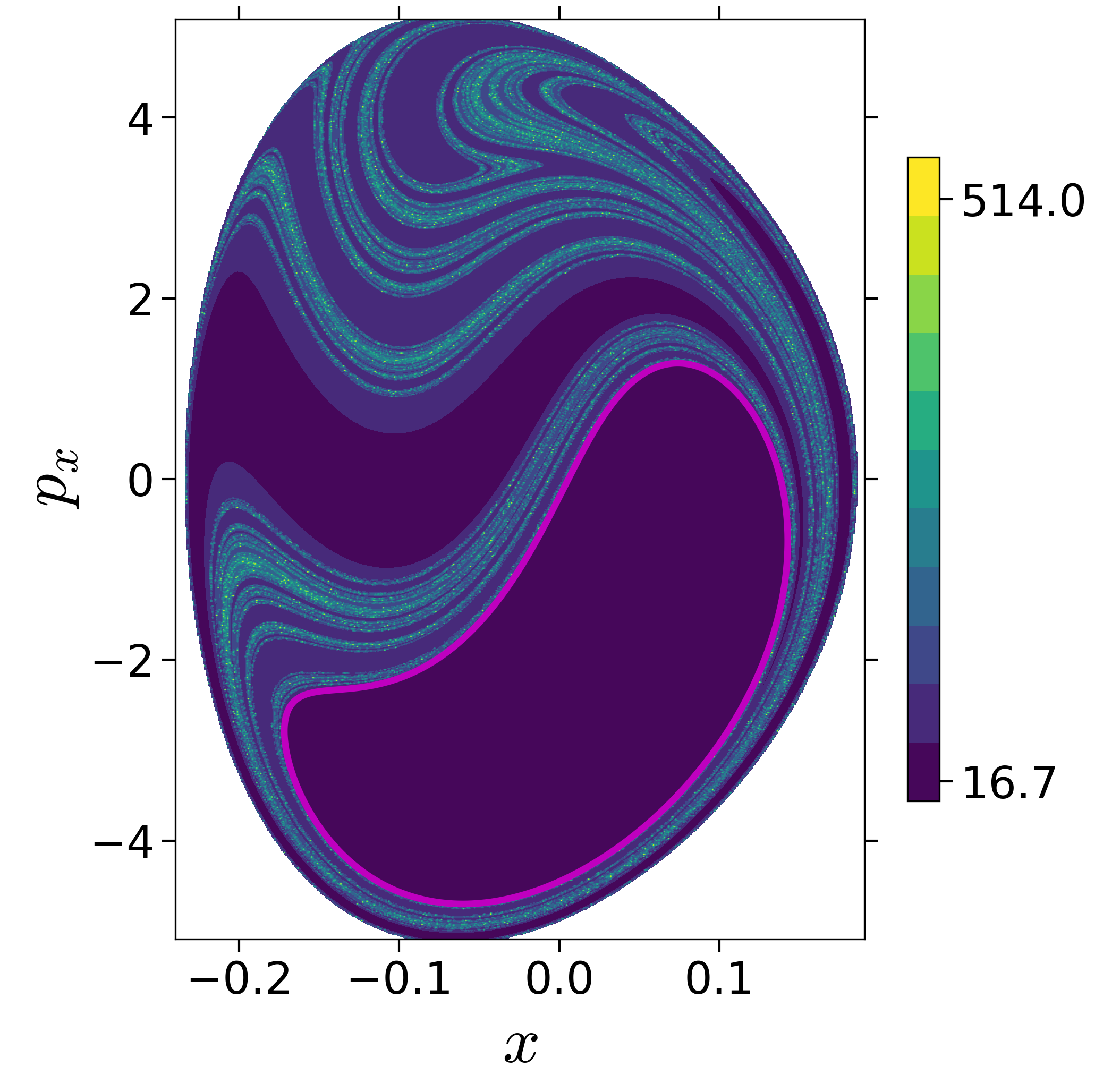

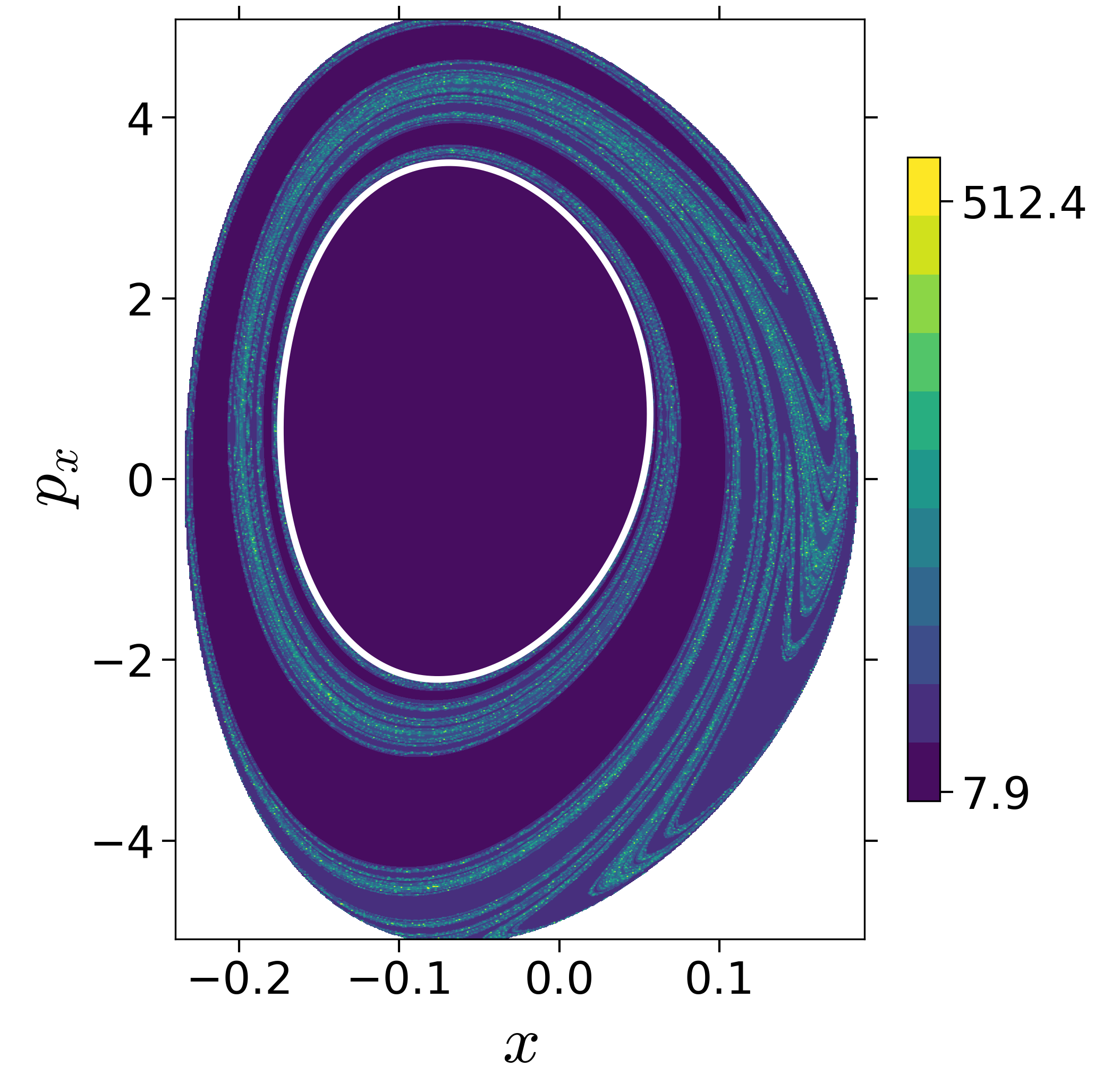

Connecting hierarchy of reactive islands with committor probabilities: Lagrangian descriptor

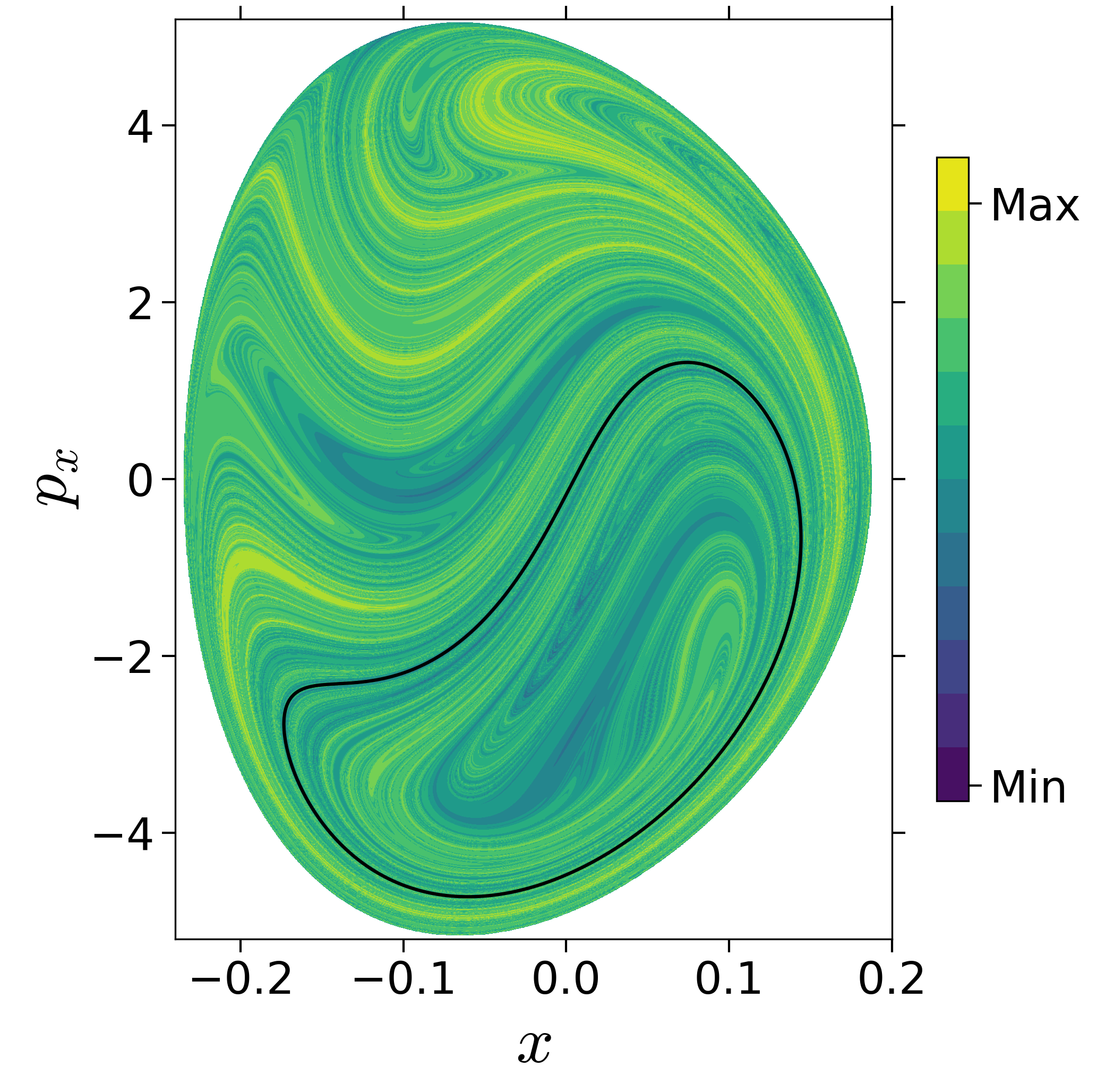

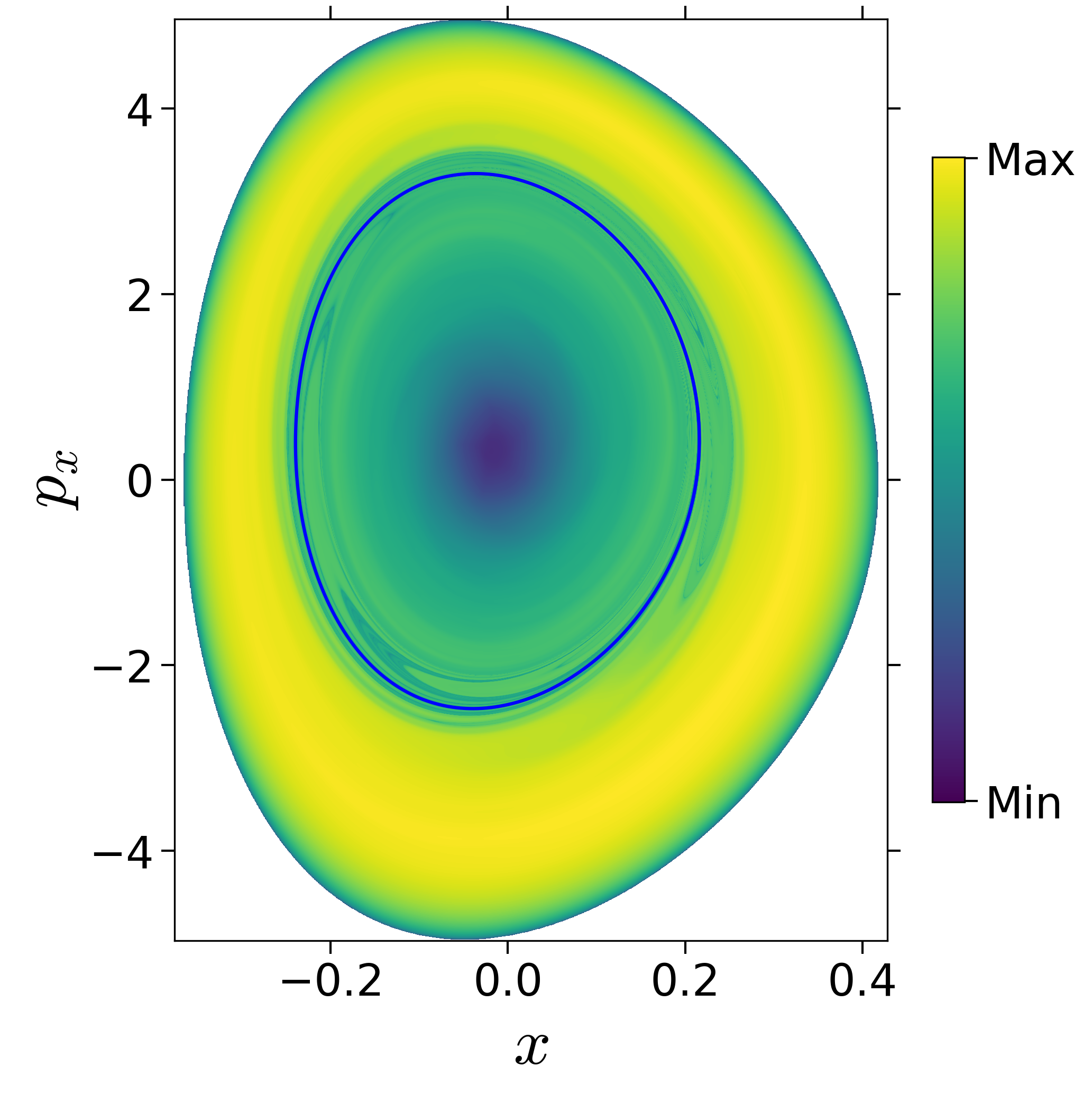

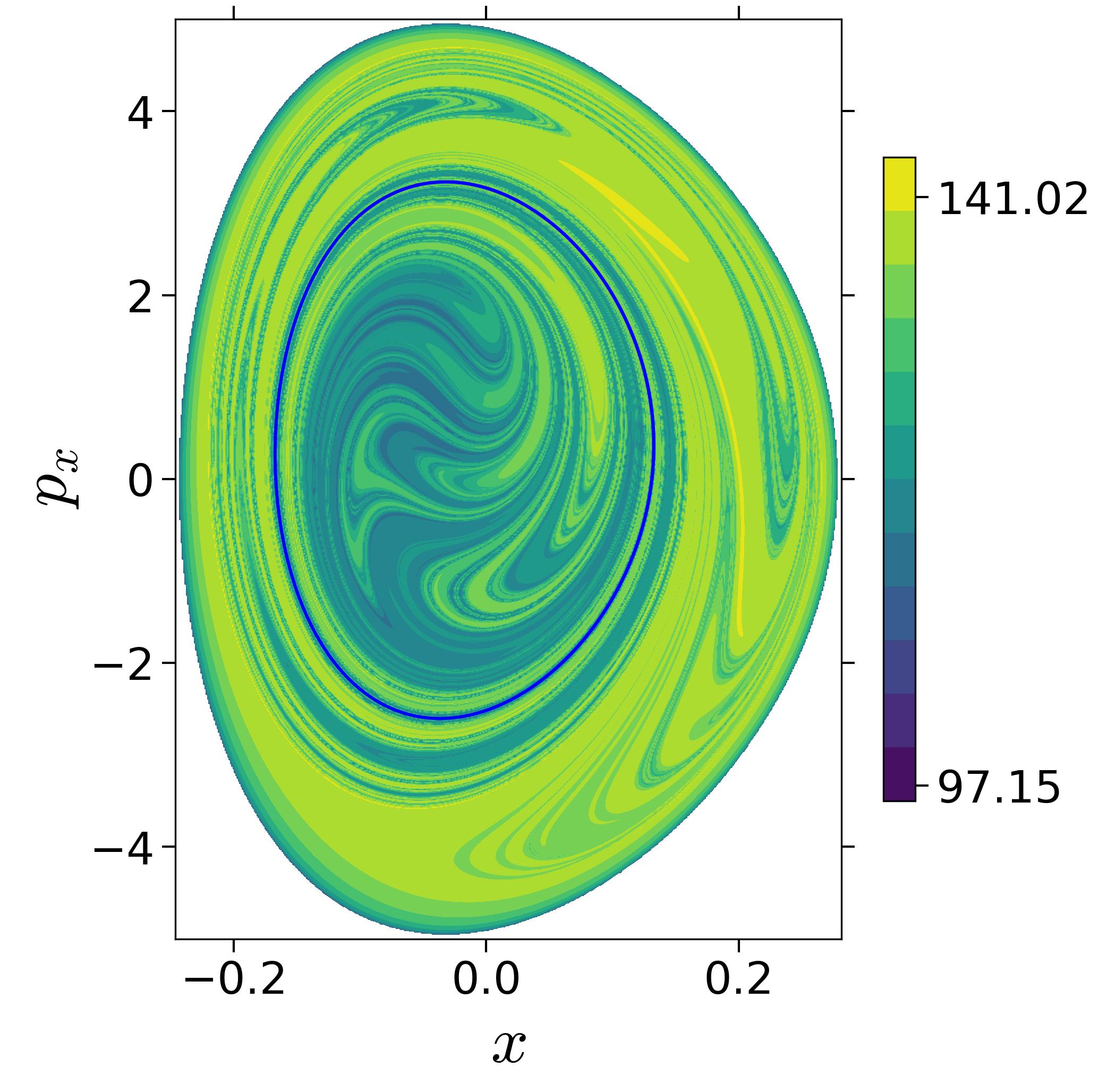

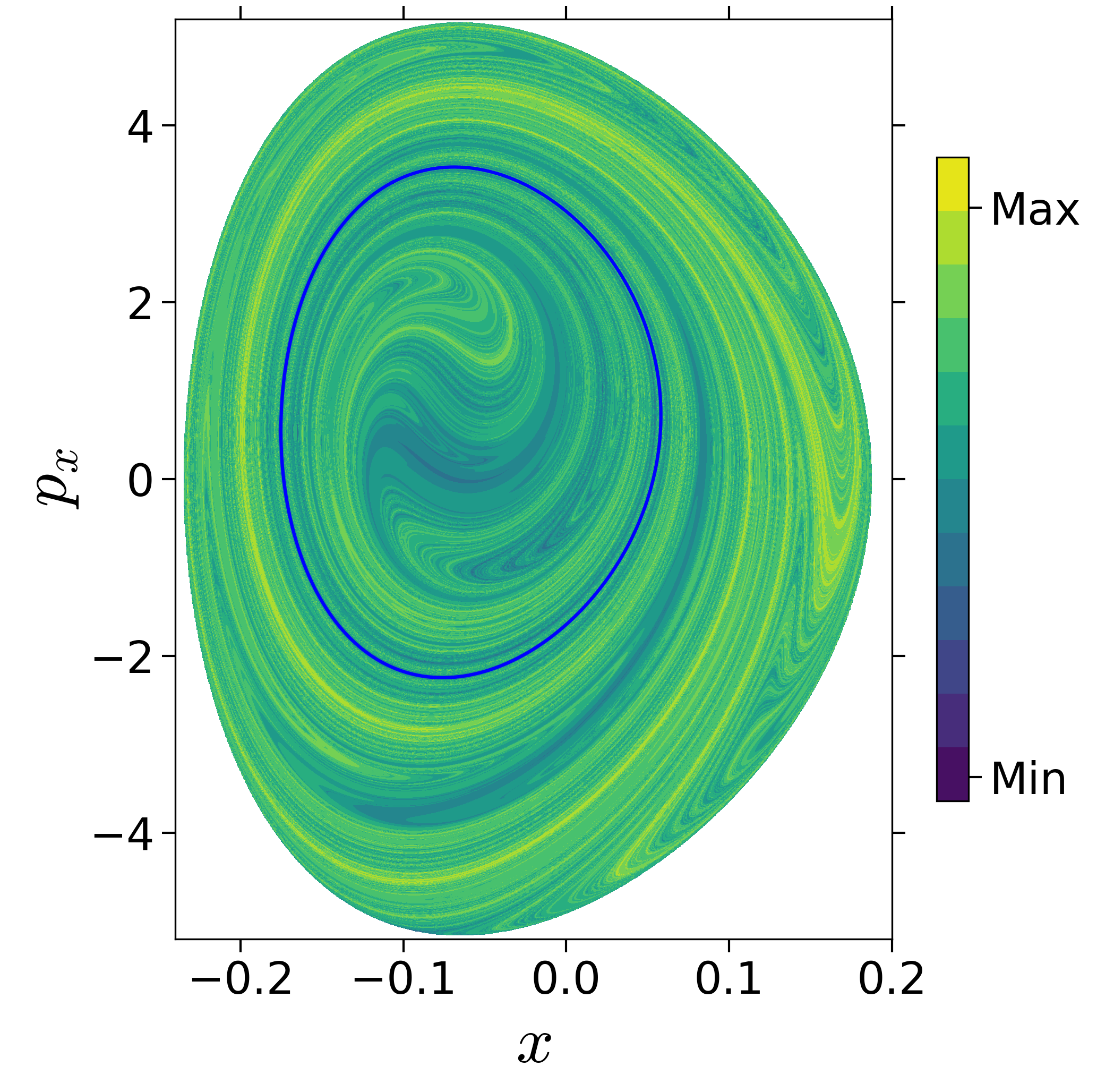

Finding reactive islands in 2 degrees-of-freedom molecular Hamiltonian has been shown using Lagrangian descriptors [9], [10].

First, we will use the following 2D isonergetic slice to compute Lagrangian descriptor contour map so that the reactive islands can be identified.

U−xpx={(x,y,px,py)|y=yw,py(x,y,px;E)<0}for 4 cases of coupling and range parameters, ζ and λ. However, we will choose the system parameters: ζ=1.00,λ=1.50 and ζ=2.30,λ=1.95 as representative of regular and chaotic dynamics of the isomerization in the gas phase.

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

{width="25%"}\

Fig. 3. Lagrangian descriptor and reactive islands for (a,d) ζ=1.00 and λ=1.00, (b,e) ζ=1.00 and λ=1.50, (c,f) ζ=2.30 and λ=1.95. The top row shows the backward LD and the bottom row shows the forward LD. The blue and black curves denote the intersection of stable and unstable manifolds with the surface-of-section, respectively, and integration time τ=30 and microcanonical ensemble of trajectories are initialized on the surface of section~(???).

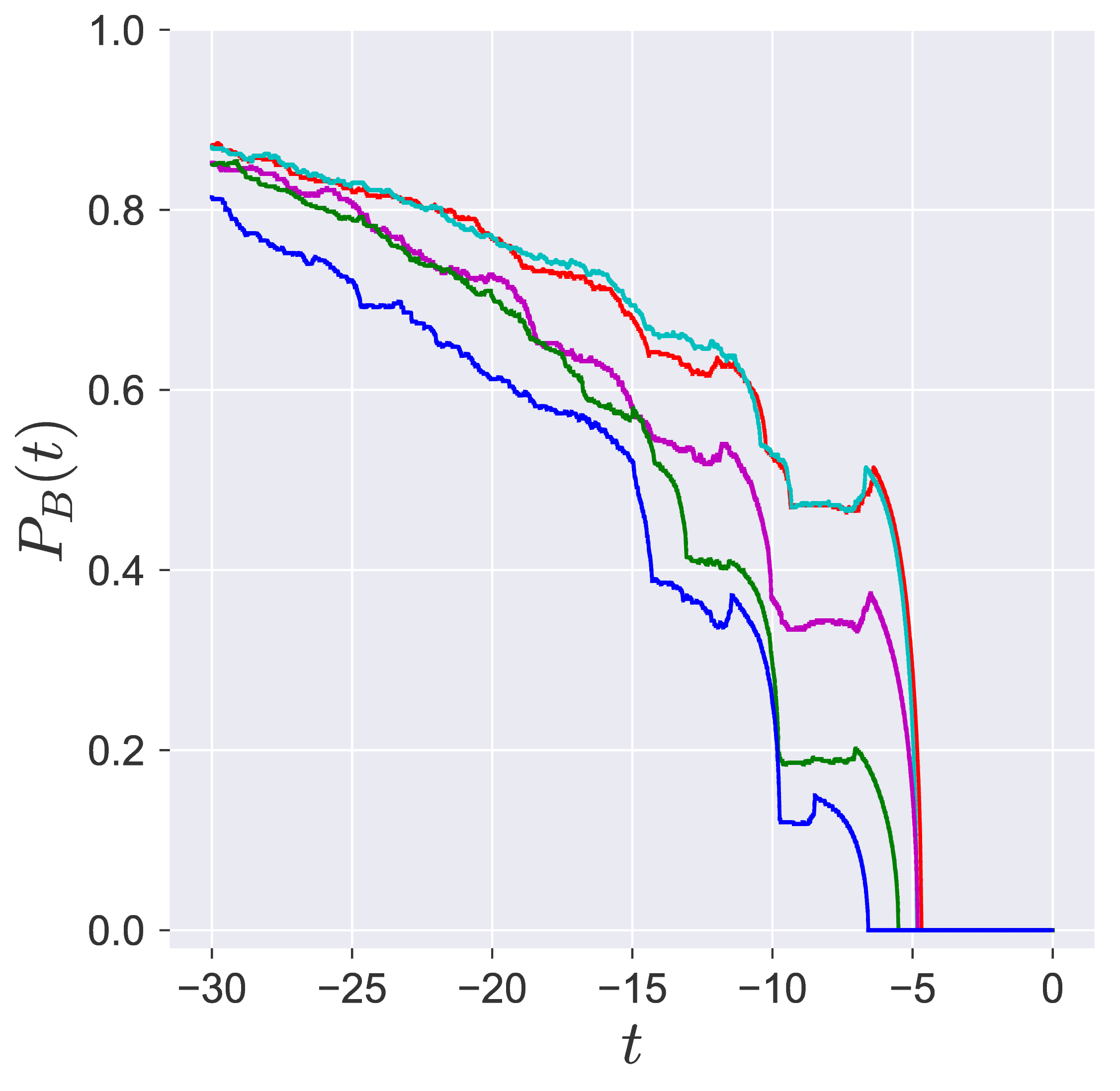

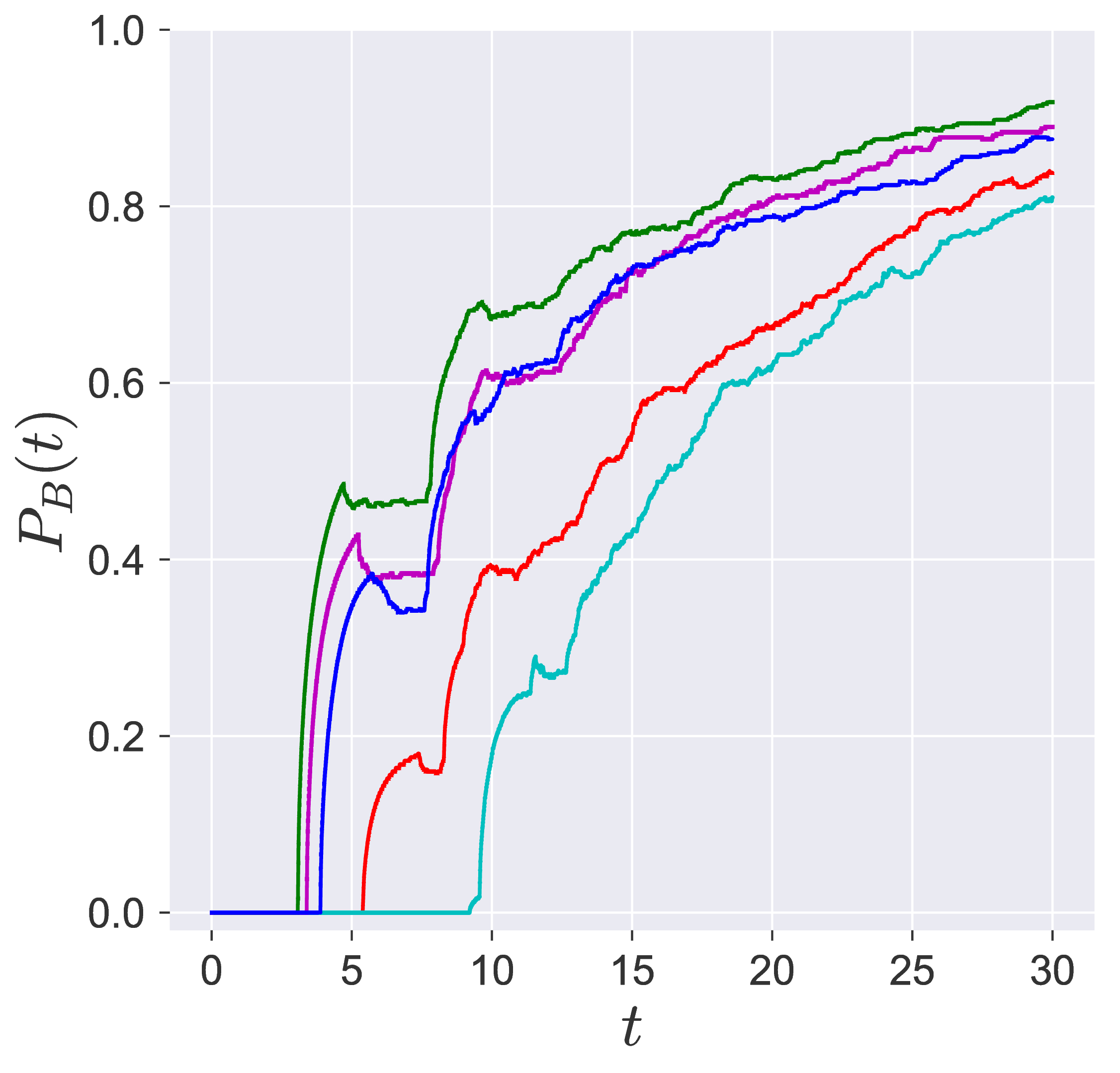

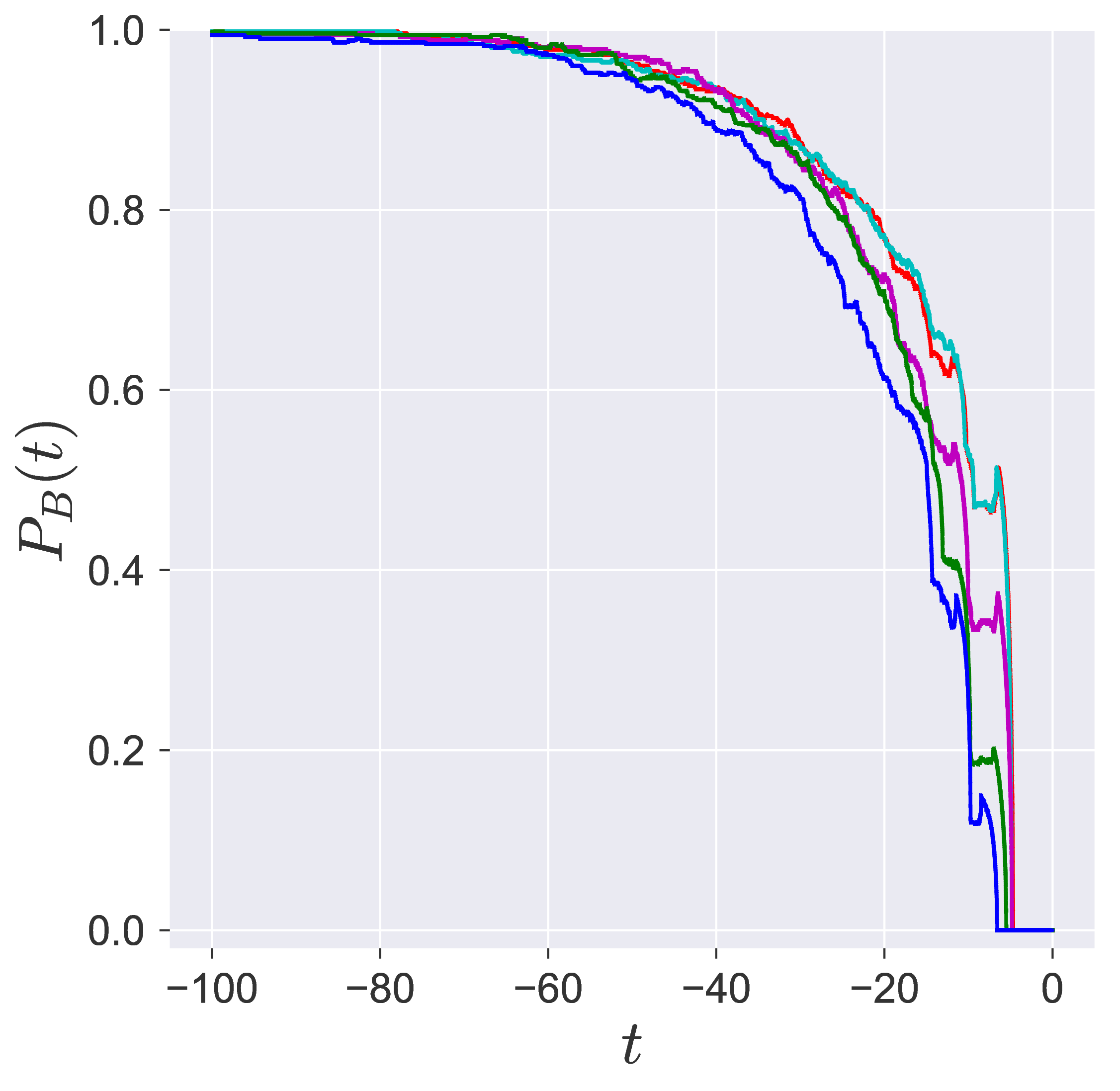

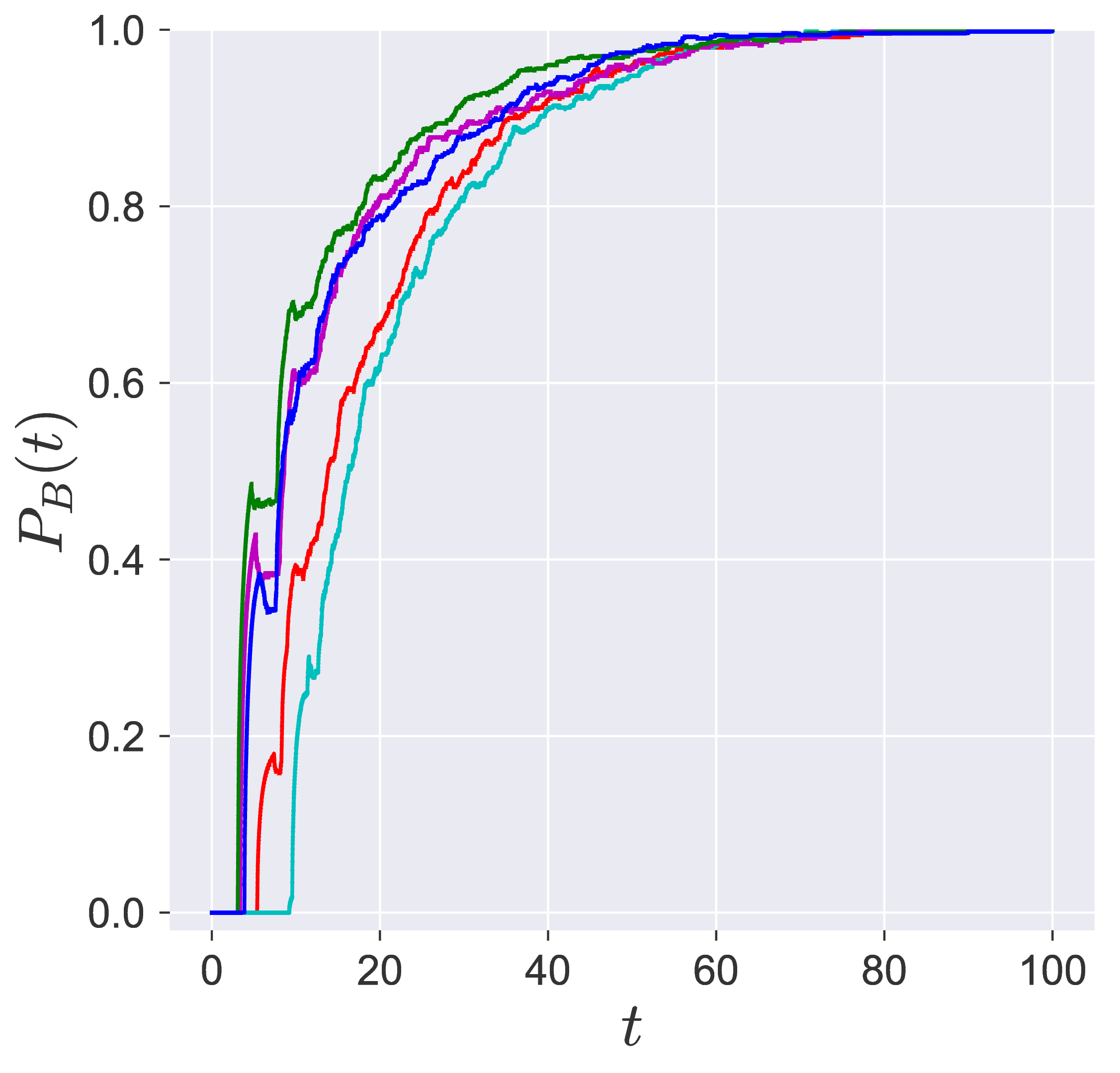

In transition path sampling, the method to check the efficiency of the sampling procedure is done by computing the committor probability of starting in region A and ending up in region B (A and B are defined in the configuration space) for the configuration qj denoted by the PB(qj,tc) [11], [9]. This is defined as the fraction of the trajectories that reach the specific product in region B at time tc before reaching reactant in region A. For the unimolecular conformational isomerization, the region A and B are defined by the isomers A and B, respectively, while the specific reactant and product configuration is defined by the parameter yw.

{width="25%"}

{width="25%"}

{width="24%"}\

{width="24%"}\  {width="24%"}\

{width="24%"}\  {width="24%"}\

{width="24%"}\  {width="24%"}

{width="24%"}

{width="24%"}\

{width="24%"}\  {width="24%"}\

{width="24%"}\  {width="24%"}\

{width="24%"}\  {width="24%"}

{width="24%"}

Probability of imminent reaction

The area enclosed by the stable or unstable manifolds of the unstable periodic orbit associated with the index-1 saddle is used to calculate the reacting population of trajectories at a constant total energy E. This population will be referred to as the microcanonical reaction probability.

For a systematic detection of the trajectories that lead to reaction by crossing the unstable periodic orbit in the bottleneck, we enforce the sign of momentum of these trajectories. So a positive ˙y=py<0 on the surface-of-section y=yw denotes crossing the

The fraction of trajectories that cross the section at y=yw in forward and backward time are unstable periodic orbit located in the bottleneck

\centering

{width="49%"}

{width="49%"}

Additional slices of Lagrangian descriptor

U+xpx={(x,y,px,py)|y=1/√2,py(x,y,px;e)<0}\centering \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E1-510_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E6-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E1-510_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3A2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E6-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \centering \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3B2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3B2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_x-px_tau30.png}} \

\centering \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E1-510_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E7-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E1-510_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_x-px_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E7-000_x-px_tau30.png}} Observation: within the τ=20 time interval unstable manifold for the second case has not fully intersected the surface-of-section.

U−ypy={(x,y,px,py)|x=0,px(x,y,py;E)<0}\centering \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E1-500_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/backward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E6-000_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E1-500_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E3-000_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E4-500_y-py_tau30.png}} \subfigure[]{\includegraphics[width=0.24\textwidth]{./figures/fig3C2/forward_lag_desc_deleonberne_E6-000_y-py_tau30.png}}

\begingroup \bibliographystyle{rsc} \endgroup

References

- N. De Leon and B. J. Berne, “Intramolecular rate process: Isomerization dynamics and the transition to chaos,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 75, no. 7, pp. 3495–3510, Oct. 1981.

- N. De Leon and C. C. Marston, “Order in chaos and the dynamics and kinetics of unimolecular conformational isomerization,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 91, no. 6, pp. 3405–3425, Sep. 1989.

- A. M. Ozorio de Almeida, N. De Leon, M. A. Mehta, and C. C. Marston, “Geometry and dynamics of stable and unstable cylinders in Hamiltonian systems,” Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 265–285, 1990.

- N. De Leon, M. A. Mehta, and R. Q. Topper, “Cylindrical manifolds in phase space as mediators of chemical reaction dynamics and kinetics. I. Theory,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 94, no. 12, pp. 8310–8328, Jun. 1991.

- N. De Leon, “Cylindrical manifolds and reactive island kinetic theory in the time domain,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 96, no. 1, pp. 285–297, Jan. 1992.

- W. S. Koon, M. W. Lo, J. E. Marsden, and S. D. Ross, Dynamical systems, the three-body problem and space mission design. Marsden books, 2011, p. 327.

- T. S. Parker and L. O. Chua, Practical Numerical Algorithms for Chaotic Systems. New York, NY, USA: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 1989.

- K. R. Meyer, G. R. Hall, and D. Offin, Introduction to Hamiltonian Dynamical Systems and the N-Body Problem. Springer, 2009.

- S. Patra and S. Keshavamurthy, “Detecting reactive islands using Lagrangian descriptors and the relevance to transition path sampling,” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 4970–4981, 2018.

- S. Naik and S. Wiggins, “Finding normally hyperbolic invariant manifolds in two and three degrees of freedom with Hénon-Heiles-type potential,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 100, no. 2, p. 022204, 2019.

- P. G. Bolhuis, D. Chandler, C. Dellago, and P. L. Geissler, “Transition Path Sampling: Throwing Ropes Over Rough Mountain Passes, in the Dark,” Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 291–318, 2002.